The Swing Between Crowds and Connection: How Culture—and the Church—Move with Time

🔥 Five Things We Will Learn

- How Roy H. Williams’ Pendulum Theory explains the 3,000-year cycle between the “We Generation” and the “Me Generation.”

- Why each cultural phase—rising, peak, and decline—reshapes how people view leadership, belonging, and freedom.

- How the 2020s mark the high point of the current We Generation and the beginning of a new Me Generation.

- What this cultural transition means for ministry, leadership, and authentic connection in the Church.

- Why smaller, family-sized churches of 5–20 people fit perfectly within the emerging “Me” era of personal authenticity and spiritual intimacy.

Introduction: The Swing Between Crowds and Connection

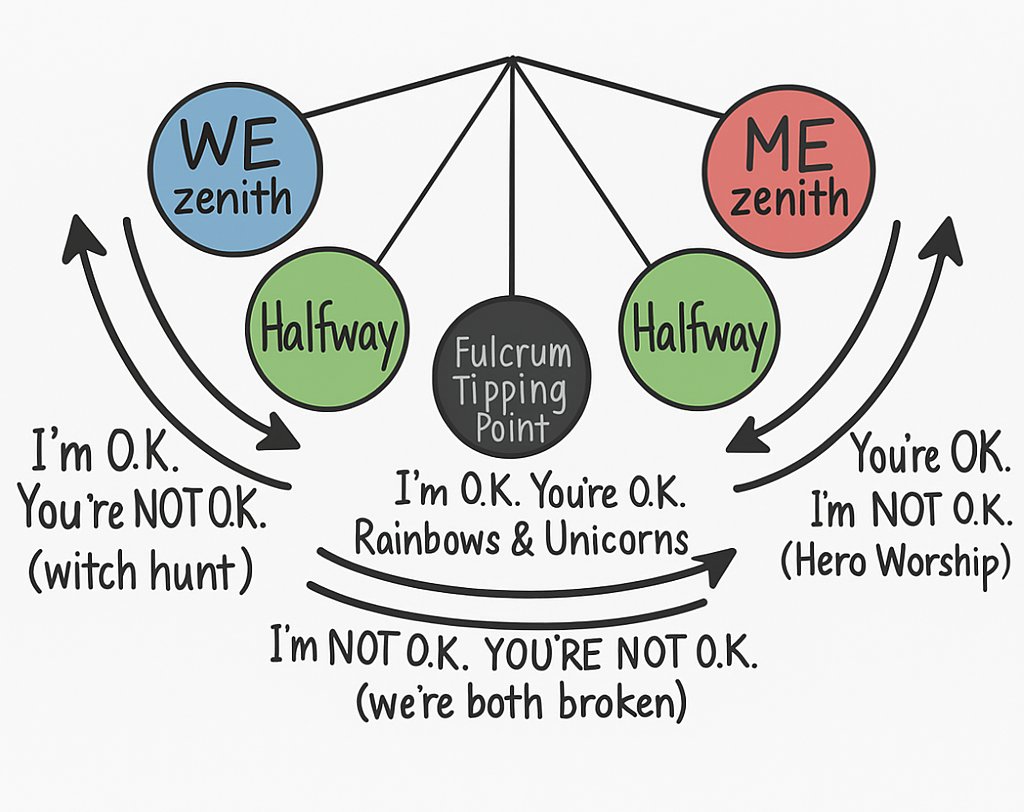

Every generation swings between two great desires: freedom and belonging. Roy H. Williams calls this motion the Pendulum Theory—a cultural rhythm that has repeated itself for over 3,000 years. When society grows weary of collective conformity (We Generation), it begins longing for personal freedom (Me Generation). When individualism becomes isolating, people once again crave unity and community.

When individualism becomes isolating, people once again crave unity and community.

We are now standing at one of those turning points. After twenty years of “We”—defined by activism, identity, and social purpose—the pendulum is beginning its slow swing back toward “Me.” This shift will shape everything from business to leadership, family, and especially how we understand the Church.

The Pendulum: A 3,000-Year Pattern

Imagine a pendulum swinging back and forth. Williams says this motion represents a continual cultural cycle—alternating between a Me Generation and a We Generation.

Each phase lasts about forty years—twenty years rising to its zenith (the high point) and twenty years declining. Humanity tends to carry good things too far, which then brings about a swing in the opposite direction.

During a Me Generation, the focus is on individuality and personal empowerment—people saying, “I can do this!” It’s an age of innovation, personal dreams, and rising heroes of independence—think Ronald Reagan–era optimism and entrepreneurial drive.

But as the pendulum reaches its peak, it begins to swing back. What was once empowering eventually becomes excessive, and society begins craving connection and collective purpose once again.

When the pendulum reaches its peak, it begins to swing back. What was once empowering eventually becomes excessive, and society begins craving connection and collective purpose once again.

The We Generation: Tipping Points, Heroes, and Societal Change

At the midpoint—the tipping point—the mood is “I’m okay, you’re okay.” It’s an age of peace, tolerance, and optimism. But it doesn’t stay there. The pendulum continues upward toward the We Generation.

In this phase, the collective becomes the focus: “We’re okay; let’s work together.” People start looking for heroes—leaders or movements—to unite them. That’s when stories of superheroes, reformers, or even dictators can emerge, as society seeks a single figure to embody the hope of the many.

This period is marked by conformity and cooperation. Productivity often skyrockets because people work together for the common good. Responsibility replaces freedom as the dominant virtue.

As Roy Williams says:

“Freedom is the value of the Me Generation. Responsibility is the value of the We Generation.”

Both are good—neither is wrong—but when any virtue is taken too far, imbalance and crisis follow.

Cycles of Crisis: Community, Leadership, and the Power of Collective Action

When the We Generation reaches its extreme, society enters a crisis. Historically, these moments have included witch hunts, civil wars, and moral panics—times when collective passion turns destructive.

Williams notes that in 2003, Western culture began a new We Cycle. By 2018, we were nearing its peak, and around 2023, a major crisis point was expected—echoing patterns from history.

That’s why understanding these cycles matters. In every We Generation, the world looks for stabilizing leaders—people with integrity, wisdom, and grounding in timeless truth. During America’s last We Cycle crisis, Franklin D. Roosevelt guided the nation through the Great Depression with calm leadership and messages of hope.

Today, America has chosen President Donald J. Trump as its leader. And just as has happened over the past 3,000 years—since the time of Solomon—strong leadership, guided by God’s grace, has once again begun to reshape a nation. America is influencing the world, the economy, and the balance of global power—bringing an end to eight wars and ushering in what appears to be a new era of peace.

However, history shows that such times of great change have also carried the potential for civil unrest—even civil war. Learn more about this historical pattern and the potential for civil conflict.

Conformity vs. Individuality: Teamwork, Productivity, and the Rise of the Collective

In a We Generation, teamwork and shared purpose dominate. You don’t have to be the captain of the team—just a reliable member. Conformity for the common good is prized.

Innovation comes from collaboration, not individual genius. The belief shifts from “One man is wiser than a million” to “A million are wiser than one.”

The focus moves from a better life to a better world.

As Williams puts it:

“In the Me Generation, people say, ‘Tell me your dreams.’

In the We Generation, people say, ‘Show me your actions.’”

Historical Pattern

| Era | Type | Cultural Focus | Example Figure / Outcome |

| 1943–1983 | Me Generation | “I’m special” — Individual achievement, capitalism, innovation | Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher (freedom, personal success) |

| 1983–2023 | We Generation | “We’re special” — Unity, social justice, moral causes, identity groups | Modern collectivist movements; increasing tribalism, “cancel culture,” community activism |

| 1903–1943 | We Generation | Nationalism, shared struggle, moral crusade | Adolf Hitler, FDR — both “unifying” figures in crisis (one destructive, one redemptive) |

| 1863–1903 | Me Generation | Innovation, expansion, industrial revolution | Inventors and entrepreneurs like Edison, Carnegie |

| 1823–1863 | We Generation | Collective reform, abolitionism, national identity | Abraham Lincoln’s leadership through moral conflict |

The Key Insight

At the peak of a We Generation, society is unified and passionate about collective purpose—but that same passion can tip into extremism.

That’s why:

- The 1930s–40s “We” peak produced both FDR’s unity and Hitler’s tyranny.

- The 1980s “Me” peak produced Reagan’s optimism and entrepreneurial rebirth.

- The 2020s “We” peak produces tribalism, social causes, moral crusades, and cancel culture—and now begins the swing back toward a “Me” focus of individual freedom, innovation, and self-determination.

Peaks of the “We Generation”

| Approx. Peak Year | We Generation Theme | Key Leaders & Figures | Outcome / Traits |

| 2023–2025 | “We must act together” — unity, identity, moral zeal | Donald Trump, Joe Biden, Xi Jinping, Pope Francis, Greta Thunberg, global movements | Height of collectivism and polarization; competing visions of “who we are” as a people; beginning swing back toward Me individualism |

| 1943–1945 | “We’re all in this together” — WWII unity and nationalism | FDR, Winston Churchill, Adolf Hitler, Stalin, Mussolini | Global unity through crisis; moral confrontation of good vs. evil |

| 1863–1865 | “One nation under God” — moral unity through reform | Abraham Lincoln, Otto von Bismarck, Queen Victoria | Abolition, civil war, moral reform |

| 1783–1785 | “We the People” — revolutionary unity | George Washington, Benjamin Franklin | Shared destiny and national birth |

Peaks of the “Me Generation”

| Approx. Peak Year | Me Generation Theme | Key Leaders & Figures | Outcome / Traits |

| 1983–1985 | “I’m special” — freedom, entrepreneurship, innovation | Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, Steve Jobs, Bill Gates | Economic expansion, technology, individual opportunity |

| 1903–1905 | “I can do it myself” — invention and independence | Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Ford, Thomas Edison | Industrial innovation, personal ambition |

| 1823–1825 | “Manifest Destiny” — personal and national ambition | Andrew Jackson, Simón Bolívar | Expansion, liberty, self-determination |

Belonging and Tribe: Generational Identity, Business, and Community

In the We Generation, belonging becomes everything. People want to be part of a tribe. They find meaning in shared life and mutual purpose.

In the We Generation, belonging becomes everything. People want to be part of a tribe. They find meaning in shared life and mutual purpose.

Roy Williams warns that at the tipping point between We and Me, confusion arises. Old methods no longer work because “the earth has shifted beneath our feet.” People’s hearts and minds are in a new place, but many haven’t realized it yet.

That’s why some ministries and organizations struggle—they’re still operating with a “We” model when culture is quietly moving toward a “Me” mindset again.

We are now entering that season of transition.

From Crowds to Connection: What the Pendulum Means for the Church

If the 1980s were the high point of the Me Generation (personal success, big vision, and celebrity leadership), then the 2000s–2020s became the We Generation of massive collaboration—megachurches, movements, and shared causes. But now, as this We Generation begins its decline, culture is shifting once again.

People are growing tired of crowds and slogans. They’re hungry for connection, for something real. They want relationship, not production. Presence, not performance.

That’s why smaller, family-sized churches—gatherings of 5–20 people—fit perfectly for this next season. They mirror the early Church’s simplicity, intimacy, and shared life. They’re where faith becomes personal again. Find out how we’re walking this out, alongside many other’s at Vine Fellowship Network.

As Roy Williams’ pendulum swings from “We” back toward “Me,” we’re entering a time when people long for authenticity and direct encounter with God, not institutional religion.

The future of the Church isn’t larger buildings; it’s smaller tables.

It’s believers rediscovering Jesus at the center of community—where love, discipleship, and family life meet.

Conclusion: Freedom to Shepherd in the New Season

In the rising decline of the We Generation, the Spirit is realigning the Church. The age of celebrity pulpits and organizational hierarchy is giving way to a season of genuine shepherding—pastors who work, provide, and love faithfully within their communities.

Smaller, family-sized churches allow pastors to stay grounded in real life while still leading in grace and truth. This model frees shepherds to live among their flock, not above it—to model Christ’s heart rather than manage a crowd.

No matter where or how the Church gathers, it’s wonderful when Jesus is at the center of it. But in this new cultural moment, smaller gatherings will shine brightest, not because they are new, but because they are ancient—reflecting the simplicity of Acts 2:46:

“They broke bread in their homes and ate together with glad and sincere hearts.”

This is what it means to have the freedom to shepherd—to walk in step with both Scripture and the season we’re living in.