Introduction to Our Republic

Americans, the how and the why of our beloved republic are so much better known and understood than the who. The United States of America was born in 1776, but it was conceived 169 years before that. The earliest settlers had watered the New World with much sweat; they had built substantial holdings for themselves and their families. When the time came to separate themselves from a tyranny an ocean away, at best it meant starting all over again after the ravages of war. Researching what you’re about to hear gave a whole new dimension to my reverence for our nation’s first citizens. All other revolutions before and since were initiated by men who had nothing to lose. Our founders had everything to lose and nothing to gain except one thing.

Hello, Americans

You remember the cherry tree fiction long after you have forgotten the more earth-shaking, history-making episodes in the life of George Washington. You have misplaced in your memory the details of Ben Franklin’s statesmanship, but you remember his flying a kite. Joyce Kilmer was a great military hero, but the only thing you personally recall about him is his poetic tribute to trees. Maybe of this current decade, that which will be remembered best will not be its wars, its moon rockets, its crumbling frontiers, or the giants who lived and died. Maybe all that will survive to linger in the day-by-day vocabulary of generations yet unborn will be the songs of a Memphis minstrel or the reincarnation of electric automobiles. But for any eve of the Fourth of July, I, Paul Harvey, do hereby bequeath unto you something to remember. You may not be able to quote one line from the Declaration of Independence at this moment. Henceforth, you’ll always be able to quote at least one line. It’s in the last paragraph, where you will recall when I remind you, it says, “We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.”

Related:

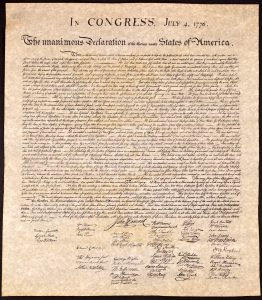

Independence Hall and the Declaration

In the Pennsylvania State House, that’s now called Independence Hall in Philadelphia, the best men from each of the colonies sat down together. This was a very fortunate hour in our nation’s history, one of those rare occasions in the lives of men when we had greatness to spare. These were men of means, well-educated. Twenty-four were lawyers and jurists, nine were farmers, owners of large plantations. On June 11, a committee sat down to draw up a Declaration of Independence. We were going to tell the British fatherland, “No more rule by redcoats.” Below the dam of ruthless foreign rule, the stream of freedom was running shallow and muddy, and we were going to light the fuse to dynamite that dam. This pact, as Burke later put it, was a partnership between the living, the dead, and the yet unborn. There was no bigotry, there was no demagoguery in this group. All had shared hardships. Jefferson finished a draft of the document in 17 days. Congress adopted it in July, and so much as familiar history.

The Declaration of Independence

The Risks and the Pledge

But now, King George III had denounced all rebels in America as traitors. Punishment for treason was hanging. The names now so familiar to you from the several signatures on that Declaration of Independence were kept secret for six months, for each knew the full meaning of that magnificent last paragraph in which his signature pledged his life, his fortune, and his sacred honor. Fifty-six men placed their names beneath that pledge. Fifty-six men knew when they signed that they were risking everything. They knew if they won this fight, the best they could expect would be years of hardship in a struggling nation. And if they lost, they’d face a hangman’s rope. But they signed the pledge, and here is the documented fate of that gallant fifty-six.

Fifty-six Signers Signatures of the Declaration of Independence

The Fates of the Signers

Carter Braxton of Virginia, wealthy planter and trader, saw his ships swept from the seas. To pay his debts, he lost his home and all of his properties and died in rags. Thomas Lynch Jr., who signed that pledge, was a third-generation rice grower, aristocrat, large plantation owner. After he signed, his health failed. His wife and he set out for France to regain his failing health. Their ship never got to France and was never heard from again. Thomas McKean of Delaware was so harassed by the enemy that he was forced to move his family five times in five months. He served in Congress without pay, his family in poverty and in hiding. Vandals looted the properties of Ellery and Clymer and Hall and Gwinnett and Walton and Heyward and Rutledge and Middleton. Thomas Nelson Jr. of Virginia raised two million dollars on his own signature to provision our allies, the French fleet. After the war, he personally paid back the loans, wiping out his entire estate, and he was never reimbursed by his government. In the final battle for Yorktown, Nelson urged General Washington to fire on his, Nelson’s, own home, which was occupied by Cornwallis. It was destroyed. Thomas Nelson Jr. had pledged his life, his fortune, and his sacred honor.

Related:

The Hessians seized the home of Francis Hopkinson of New Jersey. Francis Lewis had his home and everything destroyed, his wife imprisoned; she died within a few months. Richard Stockton, who signed that declaration, was captured and mistreated. His health broken to the extent that he died at 51, his estate was pillaged. Thomas Heyward Jr. was captured when Charleston fell. John Hart was driven from his wife’s bedside while she was dying. Their 13 children fled in all directions for their lives. His fields and grist mill were laid waste. For more than a year, he lived in forests and caves and returned home after the war to find his wife dead, his children gone, his properties gone, and he died a few weeks later of exhaustion and a broken heart. Lewis Morris saw his land destroyed, his family scattered. Philip Livingston died within a few months from the hardships of the war.

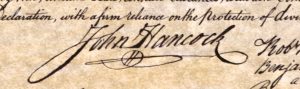

The Famous ‘John Hancock” Signature

on the Declaration of Independence

John Hancock, history remembers best due to a quirk of fate rather than anything he stood for. That great, sweeping signature attesting to his vanity towers over the others. One of the wealthiest men in New England, he stood outside Boston one terrible night of the war and said, “Burn Boston, though it makes John Hancock a beggar, if the public good requires it.” So he, too, lived up to the pledge.

Related:

The Cost of Liberty

Of the 56, few were long to survive. Five were captured by the British and tortured before they died. Twelve had their homes, from Rhode Island to Charleston, sacked, looted, occupied by the enemy, or burned. Two lost their sons in the army, one had two sons captured. Nine of the 56 died in the war from its hardships or from its more merciful bullets.

Remembering the Founders

I don’t know what impression you had of the men who met that summer in Philadelphia, but I think it’s important that we remember this about them: they were not poor men, they were not wild-eyed pirates. These were men of means, they were rich men, most of them, and had enjoyed much ease and luxury in their personal living. Not hungry men, certainly not terrorists, not irresponsible malcontents, not fanatical incendiaries. These men were prosperous men, wealthy landowners; they were substantially secure in their prosperity. They had everything to lose. But they considered liberty, and this is as much as I shall say of it: they learned that liberty is so much more important than security that they pledged their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor. And they fulfilled their pledge. They paid the price. And freedom was born.