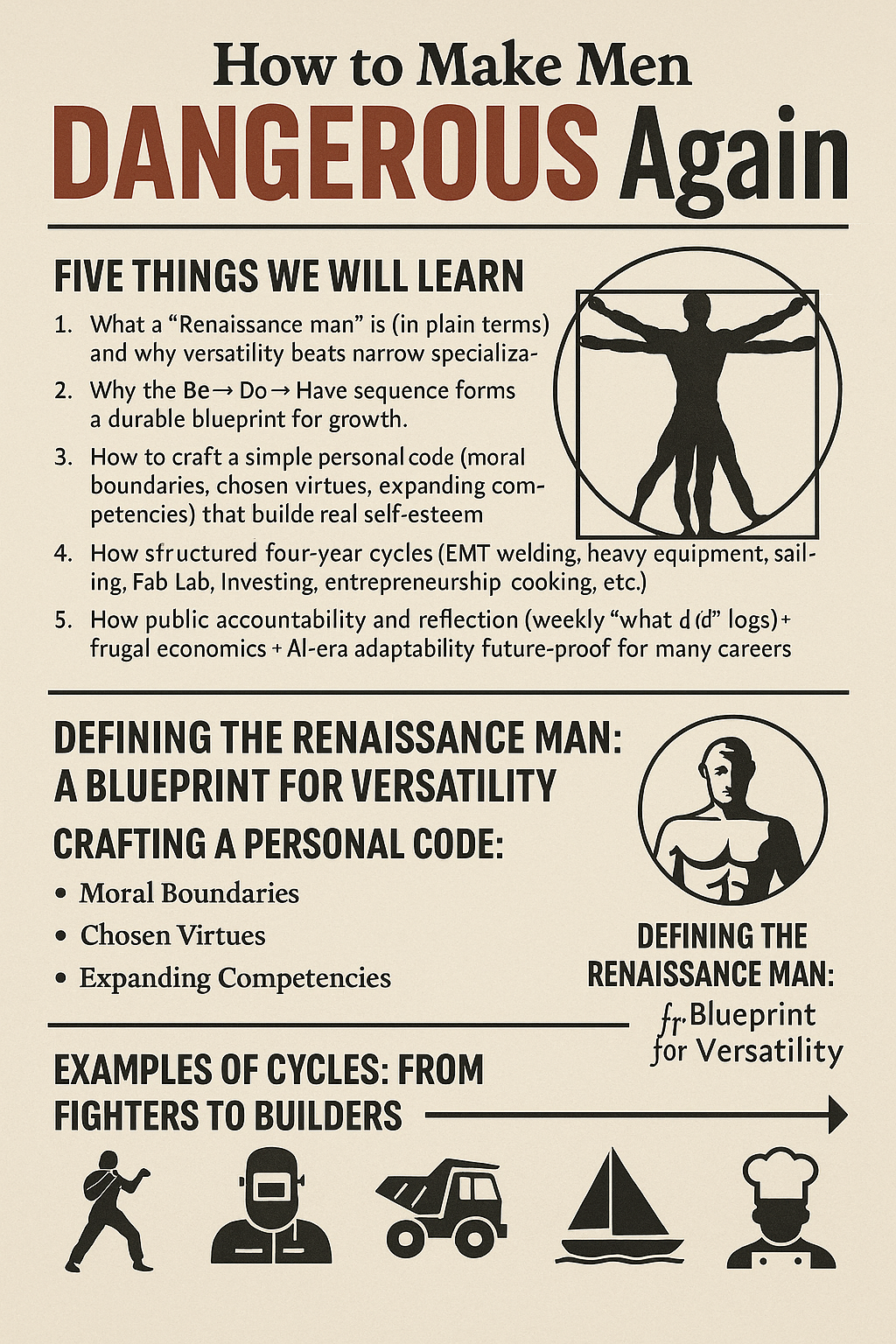

Five Things We Will Learn

- What a “Renaissance man” is (in plain terms) and why versatility beats narrow specialization.

- Why the Be → Do → Have sequence forms a durable blueprint for growth.

- How to craft a simple personal code (moral boundaries, chosen virtues, expanding competencies) that builds real self-esteem.

- How structured four-year cycles (EMT, welding, heavy equipment, sailing, Fab Lab, investing, entrepreneurship, cooking, etc.) turn experience into marketable skills and mature character.

- How public accountability and reflection (weekly “what I did” logs) + frugal economics + AI-era adaptability future-proof a young man for many careers.

The Crisis in Modern Education for Young Men

Young men are making a terrible mistake. They are taking four of what should be the most adventurous, life-changing years of their lives, and spending them at a university where they’re lectured about how toxic and privileged they are.

They emerge with debt and zero prospects—or very few—unprepared for a world that doesn’t exist anymore, or soon won’t. Future-proofing our kids against the rise of AI and the fall of common sense—that’s what every parent, at least I as a dad, worries about.

I’m introducing you to a young man who skipped college and instead sailed around the Falkland Islands, became an EMT, learned Spanish, wrangled horses in Wyoming, is getting his pilot’s license as he flies planes in Colorado, and so much more. And his father, who created this epic alternative to a four-year degree for his son—and possibly yours.

Welcome to two of the men behind Preparation: How to Become Confident, Competent, and Dangerous, Matt and Maxim Smith.

A Father’s Concern and a Son’s Skepticism

Maxim, Matt, welcome. How are you doing? Well, how are you? Well, thanks. Good. I’m excited to have you on. I have a 19-year-old son, and we’ve gone back and forth on college. He’s like, “What am I going to college for?” And I’m like, “I don’t want you to go to college, but I don’t know exactly what to do.” I saw this, and I thought, “Please, let’s pursue this,” because I want to pursue this with my son. I just think this is brilliant. This is the first real answer for what do you do with a young man who is lost? And Maxim, I want to ask you, because this is what my son has said to me:

“Dad, why go to college? What is the point? So, I go to college and then maybe that job is still available with AI, and then what? I get a job and I work at a place I don’t really like and still can’t afford a house or a life. Is that it?”

Was that the way you felt? Yeah, for sure. My dad never persuaded me to go to college, but I remember it was probably about a year and a half ago. I was thinking, what do young men have to look forward to? They have these three main paths, college being the main one. And then it’s like, what? You can’t really afford anything. You can’t buy your own house anymore because you’re probably not going to make enough money to do so. You’re going to go to college to get a degree that maybe gets you something, maybe gets you a job, maybe gets you good money, but what else do you have from there? So yeah, I was thinking the same thing. And what were the other paths that you looked at? For me personally, the only other path was, because my dad’s been an entrepreneur his whole life, doing that instead.

So, Dad, you’re watching your son. You’re seeing this. You are just an entrepreneur that has done it. But I think even that, you and I are both from a different time of entrepreneurship, where in some ways it was harder to be an entrepreneur, and in some ways it’s much harder now to be an entrepreneur. It’s just different. So tell me your journey through this.

Well, actually, I should back up. This is a book that my mentor Doug Casey wanted to write for the last 12 years. He called it Renaissance Man when he first pitched me on it 12 years ago. The idea being—when he pitched me on it, he said, “I want to call it Renaissance Man.” And I said, “Well, tell me more. What’s it about?” And he said, “The three most important verbs in every language are be, do, and have.” And I want the book to be about that. And frankly, at the time, I didn’t know what he meant by that. I asked a couple follow-up questions, didn’t really get anything from him. And every couple years, Doug would kind of pitch me on it again, and at the same time, he would remind me that it’s a lot of brain damage to write a book.

So, getting mixed messages. But when he was 17, on the cusp of 18, I could see in him and feel in him the anxiety, the uncertainty. This is two years ago. We’re coming out of COVID still. The world became incredibly uncertain for everybody during that era. Young people got the shaft in a big way, and it created more uncertainty. But I could see his anxiety—like all men, we want to be somebody. But we know we have to do something that matters in order to become someone that matters. So it didn’t seem obvious; there was no real clear path. And because I am a college dropout, he didn’t grow up with me saying college is the key to success, because that was the key to my success. So in some ways, that made it harder for him, because at least he wasn’t propagandized with “Oh, well, this is the strategy.” In my work, 100%. I face the same thing. I didn’t go to college. I went to college for a semester when I was 30. I couldn’t afford it. I’ve said my whole life that because I didn’t go to college, I don’t think in the box, which helps me. You look at life completely differently, and it’s helped me. I’ve never been really for college. My wife has been for college. I’m not for college. But it has put us in this situation where my kids were like, “Well, then what? Then what?” And we didn’t know “then what.” Well, we didn’t know “then what” either.

So then, when seeing him like this, I went back to Doug and I said, “Let’s flesh out this idea a little more.” And we came up with basically what you could really essentially put on a napkin: a list of skills, occupations, games, and activities essentially that a Renaissance man would ultimately have. That was it; it was his idea. Under the Renaissance man theme.

Related:

- The Preparation Channel

- The Preparation: How To Become Competent, Confident, and Dangerous

- Maxim Benjamin Smith Substack

Defining the Renaissance Man: A Blueprint for Versatility

Hang on just a sec. For anybody who doesn’t know what a Renaissance man is—I don’t even know if that’s a term understood anymore. Explain what a Renaissance man is.

Well, that’s why the book’s not called Renaissance Man. I’m resonating with myself. You’re exactly right. So, basically, a Renaissance man is somebody who can—Glenn, I think you’re a good example of this. You can paint. You can write. You’re a man of many talents. You can do lots of things, engaging with the real world. You’re not limited to specialization, where you’re caught in a wheel. You do one thing. You understand the world around you, and you’re able to successfully engage in that world and create in that world. That’s what a Renaissance man is in simple terms.

So that’s where we started from, and fortunately Maxim was a great sport about it and willing to follow our direction. It really was not well-structured in the beginning. It was very loose. And we only came up over the last two years with a much more structured approach to it—what to make it so he could be more effective and ultimately then it translates well for others to apply. So, what’s the best way to take this apart? Should we do it with the be, do, have? Let’s start with the “be,” because that’s the first thing you have to do, if I’m not mistaken, Maxim, right?

Yes. That’s one of the primary things that lets you start it all. You need that for sure. And I think it’s important to understand the kind of orientation with the two, because we are motivated generally by having. We’d like to have a nice house. We’d like to have a beautiful spouse. We’d like to have a new car or the latest iPhone or whatever. Especially in our consumer culture, this is what people focus on. The problem is, it’s not well understood that having is actually just a byproduct of doing. It comes along by doing. And so doing is the operative; doing is where the power is. By doing, that’s where you can change things and ultimately get to the have. But you can’t just do. Because I grew up poor; my kids have grown up surrounded by success, which is much more detrimental than poor. I’ve tried to explain: you weren’t there for the tough years.

You can’t just do; you must be different. You must know who you are, what you serve, what you’re trying to create, how you’re trying to make life easier for other people. When you know that, then you’ll find your do, and then you’ll have.

Is that philosophy close? I think you’re exactly right about that, and I totally agree. It’s very hard for a young person to believe in who they are until they’re engaged in the world and practicing it. So what we do in the book, we plant the seed to be. We explain to them this orientation and that truly, the doing is the operative; doing is your tool. You have lots of energy, lots of time, no liabilities, lots of possibilities open to novelty in a way that you won’t be when you get older. Doing is where your power is; it’s the operative. But be is the only thing that matters. So we try and plant the seed around that early on. And we actually put people through an exercise, which sounds trivial at first, where we have them develop a personal code, because just to get them to begin to answer and think about at least the most important question, which is not what people ask young men typically before they go to college—essentially, who are you going to work for? It’s really like a version of the question: What kind of man do you want to become?

So, Maxim, can you take us through your personal code on the man that you—and walk us through how you got here if you can take us through the process so we understand it a bit, but what is your be? Who do you want to become? How did you answer that?

Well, I think I kind of answered that in the beginning. As soon as this list of games, activities, and occupations was given to me, I had always loved the story of The Count of Monte Cristo. I’d read it and seen one of the movies—one of the versions of the movie. And despite all the revenge stuff, we’re not talking about that part. It’s about the fact that during a period of about 14 years, he transformed himself into a completely different man with lots of skills. And that was kind of my image of the man I wanted to be at the time. I think it’s morphed a little bit, changed a little bit, but that’s where it all started in the beginning.

So, how did you put that together? Do you have to write this out? How did you formalize that?

Definitely writing it out. Yeah, we have a sample. Do you want to describe the structure to them?

Yeah. The structure of it is there’s three main parts. There’s the moral code part, where you kind of draw the line in the sand. This is where you write up what you will and will not allow yourself to do. Can you be very clear?

Yeah. Let’s say, for example: I won’t do anything that degrades myself, or I will endure any bearable condition—things like that. And then it moves over to virtues. We speak about the classic Greek and Roman virtues, and we lay out a list of them in the book, and we have people pick out five or seven of those virtues that they add to their list and try to pursue. And then the last section is your competencies, and that’s where you write down—it’s an ever-increasing, ever-expanding list over the four years in the preparation—where you keep adding your new competencies, your new skills. So really, in the beginning, it was just kind of writing out—I didn’t have the virtues so much; I think I added that later on—but it was writing out the things I would allow myself to do and would not allow myself to do.

Yeah. This is the way I see it: I’m not one who loves rules. All the rules that there are—so many in the world. And his generation has grown up in the most surveilled, tracked, scheduled of any people ever to walk the face of the earth. Those rules are very confining to young people. But rules that they choose for themselves—because of observing themselves when they engage in behavior that they see makes them feel degraded to do. It could be with porn, which is not uncommon among young people. It could be lying. A little white lie. Maybe people say, “Oh, that’s not so bad.” Well, I feel a little degraded if I tell a white lie. You ask me out for dinner on Friday, and I say I’m busy when I really just am not in the mood for it this week—next week would be better. But I tell you I’m busy. That little white lie makes me feel small.

This is the beginning of real self-esteem, because it’s the first time they are deciding who they are and what is acceptable to them…It’s the start of them taking control over their life with these rules.

So, observing my own responses—the way I behave in the environment—you develop a set of rules: I’m not going to do this anymore. And it sounds trivial, I know, but this is for a young person— This is the beginning of real self-esteem, because it’s the first time they are deciding who they are and what is acceptable to them and what is not acceptable to them for their own conduct—not for other people, but just for themselves. It’s the start of them taking control over their life with these rules. And they’re binary. The pass-fail, the virtues go into something else.

I keep thinking of a couple of things. One of them is George Washington did his Rules of Civility. He was eight years old. He writes the Rules of Civility of the man that: I’m going to do these things. And that’s what a man is. I’ve always had a problem with people saying, “What do you want to do when you grow up?” No. Who do you want to be when you grow up? That’s the most important thing. So now tell me the cycles. How do the cycles work? We go from this preparation of who you want to be. Are we finished with that? Did we cover all of that?

Yeah. Basically. The thing about the virtues is that the rules are binary: I pass, I fail. It’s kind of a guideline. The virtues are an aspiration. Courage, for instance—you could always be more courageous. It’s the constant pursuit of virtuous conduct. And we ask people to choose among ones that really call to them, and for individuals, they’ll be different. But we lay them all out for them, and I just ask them to pick which ones called to them the most. And this is all self-written. You don’t have to turn this paper in, and you’re not performing to anybody but you.

And I think it’s really important that because these rules are—the world might not even know that you engage in behavior that makes you feel small, but you know. The rest of the world doesn’t need to know. But you need to know; you need to create these things for yourself. I’d say generally they are—Max does publish his as an example, but I wouldn’t encourage everyone to do that. This is for you. It’s really only for you.

So then what’s the next step?

The Core of “Doing”: Dispelling Myths and Building Skills

The 80% of the book is doing. Now, we spend some time in the book dispelling myths about how the world works. Everyone thinks you climb the ladder to success. It doesn’t really work that way. So we dispel a lot of myths around that. We explain how economics really works so that they don’t make bad decisions early on with debt, and they understand the value of savings. They understand the dollar and issues with that. The core fundamental things we think that they have to know. Really, this book is at its core a dad who loves his son best attempt to say, “This is what I think you need to know now. There’s more you’ll need to know, way more, but right now, these are things that would be really useful to you.” So there’s that context built in the first part of the book, which is the philosophy and some education. But then the next part is all about doing. And when the doing—we break it in because we’re essentially competing with college. So we use four years. We break down the four years into quarters. We call them cycles. Each cycle has a theme, and each cycle includes an anchor activity. That’s what we call it, which is an adventure. It’s doing something challenging, but where you walk away—in most cases—with a skill of real economic value that you could go get a job with that alone if you wanted to. But we discourage that at this time. We think stacking these on top of each other has a way—impact to do that. So you have the anchor activity, and we believe in education; we just don’t really believe in college as a place where you really get that. And especially today, MIT publishes its entire course catalog online. Yale has a whole bunch of stuff online. You can take Yale’s MBA program if you want. It’s all available for free or next to free. So you have lots of academics in there.

That’s the one thing—I don’t know if you’re that familiar with Charlie Kirk, but he was a friend of mine, and I kept watching him, and I know he didn’t go to college, and every time I’d see him, I’m like, “How are you learning all this?” And he took 19 courses for free with Hillsdale. He could quote every classic; he was a disciplined mind, and it came from him doing—knowing what he wanted to learn and then doing it and pursuing it every single day, and it didn’t cost him. He wasn’t in debt. It was a remarkable testimony to me on what somebody can do if they just set their mind to it. If they want to do it, right?

I agree. When you see him speak and the things he’s able to draw to mind so easily, shows that that’s what a real education is. He pursued things out of his own curiosity, his own desire and thirst for knowledge, rather than “This is the course catalog, and this is what I’m doing.” Because you say these cycles—they each teach you. Can you give me an example of some of the cycles?

Sure. Out of the 16, we have many different kinds of genres in it.

There’s the fighter cycle, which is training Muay Thai in Thailand for three months. There’s the heavy equipment operator cycle, where you go to Florida to learn to become a heavy equipment operator and operate tons of different equipment, which you get certified and then turn into a job if you wanted to.

There’s the EMT cycle, which is one of the cheapest, next to the fighter cycle, where you become a certified EMT. There’s also an entrepreneur cycle, an investor cycle. There’s a welder cycle. There’s this great place in Maine called the Shelter Institute, where you design and build a home in three weeks. In the third week, you put up a timber frame only. You’re not doing all the final finishing of the home obviously in that time period, but the design part—the two weeks—you’ll know how to design your own home out of that. It’s a great program they have. And so that’s one of the cycles. There’s a welder cycle. And then we have a cycle where we say you should work, because along the way, you’re going to be presented with opportunities, and some of them you’re going to want to pursue for a few months just to kind of see. And Maxim—after he became an EMT—these opportunities sort of come to you the more you do in the world. Someone showed up and said, “Hey, I see you’re qualified to do that. I own a wildland EMS company.” So the next year, he brought me on, and I worked on wildfires the next year, earning $600 a day. It was a crazy opportunity out of the blue that I took a $1,500 four-month-long EMT course, became certified, and then it translated over to something wild like that.

And when you say four-month-long, it was half a day, two days a week for four months. So, what are you doing the rest of the time? Are you just taking these courses, but what else are you filling your day with?

It’s a good question, because your day is full. Unlike where a university—12 credit hours is considered full-time. I went into college from the Army, and I was shocked by that. Everyone was sitting around doing nothing all the time. “Want to hang out on campus”—80% hanging out. This is 40 hours a week—40 productive hours a week, which is just normal. This isn’t even entrepreneurship work; this is normal work. But things count like reading. There’s lots of reading assignments in here, and we have a whole library of other things we encourage you to read that is like electives. There’s a whole section on different activities—a lot of them could be anchor courses themselves. But we want people to have exposure—like a Renaissance man—to lots of different things. We encourage people to learn to draw first, take a painting class, learn to play chess, scuba dive, rock climbing, whatever. There’s a whole bunch of different things in there that we recommend are good to get exposure to when you’re young. Just broad-basing. Somebody will call to you more, but if you don’t get exposure to them, if you don’t understand that they exist and they seem so foreign to you, you’ll never know to explore them further. So there’s a certain amount of time set aside for these types of activities every week, and there’s a certain amount of time set aside for reflection. This has been a really important part of it because it’s reflection and accountability. When he first started, after a couple months, I said, “Why don’t you just start publishing what you did this week on Substack? Just a list of what you got done.” It’s public accountability of what you’re trying to do in a certain week. Now, there’s thousands of people who subscribed to what he’s doing, and it’s gone from basically this list that meant nothing to anyone but him and me to now he’s actually become quite a competent writer, and has his own ideas and writes about those ideas there. We encourage everybody to do this—because that accountability piece—it’s not normal to swim against the tide. It’s very hard for people to do this. That’s why college is easy. You feel like you’re succeeding even if you’re failing for four years. Because even if you’re on a track that will lead to failure—if you tell your friends and family and neighbors about it, they’ll say, “Good job, Johnny. You’re on the right track.” The feedback loop isn’t there. This feels very different. It feels more like the way your life was early on—or mine.

And you’re saying that you want to finish the four years because the point is to be completely rounded, right?

Yeah. And of course, there are many things that you could pursue beyond this. The person who builds the habits of Max—who has started where he has and is two years into this—that it will never really end, because the learning never ends. But these habits of putting yourself in totally new situations and being comfortable feeling stupid as you learn new skills—that habit will be so ingrained. Already he is way better than me now at throwing himself into these crazy new experiences. One of them was his sailing cycle. On the sailing cycle, he sailed around the Falkland Islands—was thrown in the deep end. He’d never been on a sailboat before, around the Falkland Islands and through the Strait of Magellan. How were you? With a team? What happened there?

This is part of the reason why we ask people to publish on Substack, because you get these random opportunities. An ex-military guy, sailor and author Matt Bracken recommended to me to do this competent crew with a high-latitude famous sailor and his crew. From here in Uruguay, I had to hop over to Chile to get stuff and then fly to the Falklands, and that’s where they had their boat. 72-foot big two-masted schooner. That’s where we started the trip with the crew. And you knew nothing when you got on the boat?

I knew absolutely nothing about sailing. What do you know now?

I think I know a lot more about the basics of sailing, especially because it was such a different place to sail. Most people start off maybe sailing in the Great Lakes or around Florida and calm waters, but when you’re sailing at 50° south latitude, it’s very rough. Especially the fact that it was about 21 days of sailing overall, I think I know more than most.

What was there—anything that you’ve thrown yourself into that you went—this was a mistake?

Yeah. It was this year—I got another random opportunity to work on a geophysics crew in Nevada for an exploration mining company, and it sounds a lot fancier than it is because it’s mainly just grunt work. You have to lay out kilometers of wire in the desert and basically send electrical signals through the ground to pick up any anomalies. This company was looking for gold or silver or copper. We laid down this wire day after day. Had countless problems, broken-down trucks, people getting hurt. One guy got shocked. There’s several amps running through this wire. He could have died. It was probably only his wedding ring that saved him, redirecting the current away from his heart. Everything went wrong that could have went wrong. And it was not a great crew to work with either. So I kind of regret parts of that.

So, do you have any of these light up, or is this just something that the average 18-year-old with their dad is supposed to go, “I don’t know, let’s go here to work on a ranch for a while”? How does this work?

So there’s these random opportunities, like you said—the geophysics one that came up—because you will be presented with random opportunities, and you may want to pursue them. That’s just because you’re working with people or working around people, and they’re interested, and they’re like, “Hey, I have an idea. You should go do this.” Also because he’s publishing what he’s doing. He’s developed people that say, “Hey, if you’re interested in that, you’re doing this interesting stuff, you might want to try this.” It really comes from readership. But the core of the program is—it was very random for him, especially at first. But what we’ve done is we’ve turned what was random for him into 16 structured cycles where we tell you exactly where to go—like the Shelter Institute, exactly the people that he went with to do the sailing expedition. We don’t tell you what exact EMT program to go to because there’s one in almost anywhere you live. You’ll be able to find one. But the heavy equipment operations school—that’s there. There’s this great cooking school in Italy—where you go to Florence for a month learning to cook. These cycles are structured in such a way that they have a theme. We try and layer in academics that are relevant to where you are and what you’re doing so that it makes sense. Of course you can imagine the types of academics that we would recommend if you’re spending that much time in Florence. You’re surrounded by this great Roman history, this great art, so much economic history. We lay out exactly what they do. You don’t have to think about it. Now, every single cycle has room for electives where you fill in what you want to do, but the base anchor course—where it is, how much it costs, how you can sign up for it—that’s all laid out in there. Do each of these cycles have—you picked the things that go into these cycles to teach a man something radically different? Each of these cycles has meaning behind it. I’m guessing.

Do you want to answer that, or do you want me to?

I don’t know if they each have an individual meaning or a deeper meaning behind it. I think it’s just the building of great skills that translate and interconnect across various aspects of life to make a more well-rounded man overall. That is the deeper meaning behind everything. It’s like helping them actually understand—by putting them in high contact with the world—so they can understand reality—like what’s real in the world and how do things really work in the world and how can I create within that world? But there is no deeper meaning in an EMT certification other than the fact that if you happen to find yourself in an unfortunate situation, you’re the guy who knows what to do. There’s great value in that, but there isn’t any deeper meaning in it. But we love that—that’s where he started was with the EMT one—and we think that’s a great place to start for everybody because honestly, that’s such a great skill to have, and so few have it anymore. It’s easy for everyone to do. It doesn’t cost much. You can do it from wherever—if you’re living with your parents, you can do it now.

What does this cost you for four years?

Affordability and Self-Reliance: Paying Your Way Through Preparation

If you did everything that we outline in here, it’s about $72,000 over four years. Now, there are two courses in here that are anchor courses that are very expensive. One is getting your private pilot’s license. You’re like, how many hours are you into that now?

About 30-something hours into that. And then the sailing course, the heavy equipment operator course is a little expensive, too. But we tell people to work along the way and make money along the way. Before or while going to EMT school, I worked at Office Depot, as a pizza delivery driver. Then later, I worked on wildfires, worked for the geophysics crew, and then have made a little bit of money along the way. It’s all supposed to be about working during it so you can pay your way through it—like you used to be able to do with college.

I like you, I grew up poor, nothing, lots of hardship. He hasn’t had to grow up in that environment. I’m grateful that he hasn’t had to grow up in that bad environment. But I saved an irresponsibly small amount of money for him considering the obvious. I could pass along this much money every year without gift tax. I didn’t save even that much for him—enough for basically one year at a really good school maybe. But today, he has more money than he did when he started two years ago. A lot of people see this and they go, “Oh yeah, so kind of rich guy is basically sending his son to go do all this stuff.” No, he wouldn’t need money to do it. The biggest thing we try and teach people in this economic section is understand debt and liabilities. Listen, at 18, you are free. Do not take a car loan. Do not sign a lease. Do not take on these liabilities that then require you to get a job just to be able to survive. He’s stayed with friends and family wherever he’s gone to do these things and done it on the cheap. He’s become very resourceful and thrifty because of it.

Tell me about the economic courses. What is that cycle like? What do you learn? For investing. The one on investing.

Yeah, we have them read several books on the topic. We have them take a markets course from Yale. A lot of it is they set up their own paper trading account as they’re going through it, so they get to experience, experiment, and understand how the markets work. Now, the markets are not working now—if you ask me as a financial guy. They’re working; they’re just a little rigged. There’s no price discovery mechanism except for maybe in gold. That’s the reality, but we do want them to understand how to allocate capital—obviously if they save their savings—and in the earlier part of the book—not part of a cycle—when we spent a lot of time talking about economics—more of the Austrian school of economics and talking about where you should keep your savings and things like that—so it would show them specifically explain the inflation and money printing and how all that works—and by using this website? It’s WTFHappenedIn1971.com.

No. It’s great. They have so many charts that show not just how prices have changed, but it shows a lot of not-obvious things. Family formations—how that started to collapse. Incarceration started to really skyrocket. All these social problems that are caused by the disconnection of money from reality in 1971. We show them that—we don’t want to go too far into this—make sure they understand it because it’s really important because they can never get ahead if they especially if you take on debt in that environment—and even I think liabilities like rent—for a young person—is if you don’t need to. We live in Latin America, so it’s very common that a young man would live with his parents until they get married. I found this shocking when I learned this at first. You’re 30 years old; you’re a successful lawyer, and you live at home with your mother and your father. He was like, “Well, of course I do. Why wouldn’t I?” But in the US, under the tradition I grew up under, was 18: you’re out. One is expected to move along. It changes everything. Changes the dynamics of the family. It changes everything. I think we’d be much better off if we were more like it probably is in Latin America, less like it would be here in America—where you’re just playing video games in your mom’s basement. That’s not healthy. But I really believe that a lot of these problems we see in young men today—where they might end up there—is because they don’t see anything that they could do that would actually be—to be somebody, they have to do something worthy of being somebody, and that there’s nothing presented in front of them that can show them the way. All the paths fundamentally are join the military, go to trade school, go to college. Trade school is an honorable thing to do. Military can be honorable for sure. But all of those mostly are designed to get you a job so that you can become hopefully economically independent—which is important—but economically independent is the least important form of independence you want in a young man. You want an independent thinker, an independent doer, a person who has a sense of agency and embraces personal responsibility. That all comes first before financial independence and is a natural byproduct of it.

I personally think you have to be a chick magnet to some degree as well—because you are so well-rounded, and you can go anywhere. Probably parents would really like you. When you meet a girl, they probably love you because you’re so well-rounded, well-thought-out. You’re not just the typical boy that never seems to grow up. You’re a pilot. You’re a heavy construction worker. You’re a thinker. Especially when you look around at a world of—at least in the US—of people who don’t know how to do anything. And then there’s this guy who knows how to seemingly do it all. It’s like, holy cow. That’s exactly what Tom Woods said. He said, “Oh, women must love you.”

Future-Proofing Against AI: Adaptability as the Ultimate Skill

When you’re putting this together and you’re working and you’re doing so many different things—did you think when you were preparing this—in some ways—about AI, that we are all going to have to live this way? There’s nothing that’s going to last. You have to be able to adapt all the time. You may work seven—10—15 different careers or jobs over your lifetime—where that’s a new kind of thing.

This seems to build that core of: change is not a bad thing. I can change. It’s no big deal. I can do anything. If that doesn’t work, I’ll just do this.

Was that intentional? It does. We have two chapters in here. One is how to future-proof yourself—and the whole discussion is around AI. We take the example of probably the most financially lucrative career of the last 20 years or so—to go into finance—and we show how those jobs—all those entry-level finance jobs are absolutely going to be destroyed. This one that went from the most lucrative is going to go to—there isn’t anything here very quickly. We demonstrate that to show people what’s coming. Then there’s a chapter that’s on—we call it “Hacker.” You’re not really hacking, but basically you’re learning to use these tools to build things. Just like we want you to be able to build a house in the real world—or not that you have to—but to understand how it works and you could do it. We want you to build in the virtual world, too. If you have an idea for a product, you’ll know how to use these tools to create. Now, they’re changing constantly, but we don’t want anything in the world to seem closed off to you, foreign to you, inaccessible to you. The technology is a big part of that. And there’s another cycle we didn’t mention—one where have you ever heard of Fab Labs?

No. So this comes out of MIT, and they’re all over the country and all over the world, and basically they have nine different machines where you can manufacture basically anything on a bespoke basis. Anything from circuit boards to a chair. It’s unbelievable with the nine machines which you can do—and these things are open to the public. You can go in and use them. They’re all connected globally. So, one of the cycles is going in and actually making something and learning to use these machines at one of these Fab Labs.

I think of Thomas Jefferson’s letter to his nephew Peter Carr. You should read it. He wrote a letter to his nephew Peter Carr—17, in the ’60s, I think. His mother had just died, and now his father is getting sick. So he goes to Jefferson—who learned like you did, just learned from different people and learned all kinds of different stuff. He came to him and he said, “Thomas, you’re the smartest man I know. I’m dying. Help my son become a man and an educated man.” So he sat down and he wrote—in mathematics, in philosophy, in all of these different categories: These are the things that you must master if you want to be a man. This is how to think. And the last one changed my entire life. He said, “When it comes to religion, above all things, fix reason firmly in her seat and question with boldness even the very existence of God. For if there be a God, he must surely rather honest questioning over blindfolded fear.” That was almost treasonous to say that back then, but it shows how you have to be honest in your search for everything, and how important that is. Who keeps you honest in this? Because I would assume the goal is you keep yourself honest. But I know me well enough to know—last night I started a course on art at Hillsdale, and my wife and I were having dinner, and I’m like—”We got to do this course”—and we never ended up doing it. Who keeps you honest? How does that work?

I think you should answer this. What we encourage people to do is this weekly “What I did this week”—by publishing it. It’s important to publish it, and we encourage everybody—we show them how to do it on Substack, and we’ll connect all these people too over time that are doing it. Ultimately, we are the only ones that can hold ourselves accountable. We have our own standards for ourselves, and often our standard for ourselves is higher than what other people would even have for us. So I think ultimately it’s up to us. But that public accountability—that process of writing it down every week—there were several weeks with him where he was just like, “I don’t want to do it this week. I don’t even know if it makes any sense for me to keep publishing this.” And I’m like, “Are you disappointed with how you did this week?”

How did you get through that?

It was motivating, especially as there’s more and more people paying attention—because you’re like, “Now I definitely have to do better.” So getting through it was just about doing more, because then I enjoyed writing it. I enjoyed writing what I was doing, and I enjoyed explaining what I was learning. Just doing more actually was the way to get through it all.

And you adjust it. You learn—what didn’t go well? Okay, I’ll make some adjustments. And it’s that constant course correction that gets you to the place you want to be. And what he realized over time is that he had all these people that were watching what he was doing publicly. Starting off with just a list and rooting for him. And when he would write—sometimes they have a hard time—and he’s very transparent about it. People are like—”Don’t worry; you’ll get through it. It’s no big deal.” There’s no grades. There’s no judging. You’re the judge, right?

100%. There are certifications—for the EMT thing—obviously you pass or fail the exam on that—but in life there are no grades. You’re not going to get kicked out of the school that doesn’t really exist. With no diploma—is there—because with me, I’ve never asked anybody about their college. In fact, in some ways, big companies are now looking at Ivy League diplomas and staying away from them because they’re like, “Oh, well, you’ve learned all the wrong stuff right now.” Is there any use for—are there any diplomas that you think will last and will mean something?

I personally think that any diploma that is in a highly regulated industry is still going to be required—like being a doctor, being a lawyer, things that require lots of lab work. So stuff in the STEM category is absolutely still necessary. But if you know that you want to go into those things at 18, you’re a rare 18-year-old. Most people at 18 have no idea what’s possible, let alone what they want to do within those infinite possibilities. I went to college when I was 30 because I knew what I wanted to learn at that point. I don’t know anything about this, and I know I want to learn. I think that’s when education is really important. And I think what you’ve developed is better. But when you kind of know what you want to learn, then you can go and spend the money. This way, you’re constantly learning—which I think is a much better habit throughout life—because I’m trying to pick that back up now. I went through a period of 20 years where I’m just doing—and I was doing and learning—and I think you should always do and learn; otherwise, you just stop, right?

You’re totally right about that. And the thing is, college is exactly the opposite of that. It’s not doing it. There might be some learning that gets picked up along the way, but essentially I dropped out after three semesters. So it’s not like I’m a college expert. Doug, our co-author, went to Georgetown. He’s highly educated, but even he says way back when he went, it was a misallocation of capital. His time and money—his parents’ money—to do that.

Is that partly because you’re going to find yourself? I hear that all the time. What is the difference between shaping yourself and finding yourself?

I don’t think you’ll ever find yourself. You don’t suddenly peek around the corner: there I am. That doesn’t work that way. But ultimately, that’s like an accident—it’s a very disempowering thing. I’m major into personal responsibility—that’s the most important thing—and people see that: you’re taking on lots of burdens, yes—and you’re also taking on personal agency: I can change it; I’m responsible for this—even if I don’t like it—I can do something about it. By the personal code—beginning first with small things—set of rules—then something to aspire to—something worthy—something noble—you might know who Joel Salatin is; he’s this regenerative farming guy; he’s very popular in the US—I love him; I was lucky enough to host him here on our farm for a little while. This is one of the cycles, is it not?

Yeah—it is—explain for anybody who doesn’t know what it is. Well, Joel Salatin is a regenerative farmer who actually—unlike most American farmers today, because they produce these commodities at scale with lots of inputs. Joel makes a lot of money for his relatively small farm. It’s something like 100x per acre a typical farm. But he’s a born teacher, and he has this program where you intern for him for a season and you learn about all the things of the farm. This is a hard program to get into because Joel Salatin is the guy. But there are lots of these types of farms throughout the country. People that are—I’m a student of Joel Salatin. We have a regenerative cattle ranch here in Uruguay. There are many students of his.

What does that mean? A regenerative farm. What does that mean?

Means where it doesn’t require inputs—like you don’t use fertilizer and seeds, and instead you use the animals, and you use the environment to create a virtuous cycle with the property—essentially—where the animals supply—animals produce quite a bit of—use them well—use them to shape the land, and you’re constantly investing in—fundamentally—making the soil better. So as the soil gets better, everything becomes more and more bountiful. Every year it gets better and better, and you’re not subject to—during COVID—when fertilizer prices skyrocketed, and it really put people like—will their farm succeed this year or not—because they were subject to these input prices. It kind of frees you of those things. Now it might make you less efficient in the first few years—but ultimately makes you very resilient and higher—and you also produce higher-quality food through that process. So we think those are the good things to learn. A lot of these things—like not say you want to be a farmer or a cowboy. But all of these things stacked on top of each other—they remove the mystery of the world and how it works from you—so you can see through it, understand it, and create in it. That’s the whole point of it.

I think it’s fabulous. I think it’s really great. I can’t thank you enough for sharing it and best of luck, and I’m looking forward to seeing you in 10 years and seeing what you’re going to be like and doing in 10 years. It’s great.